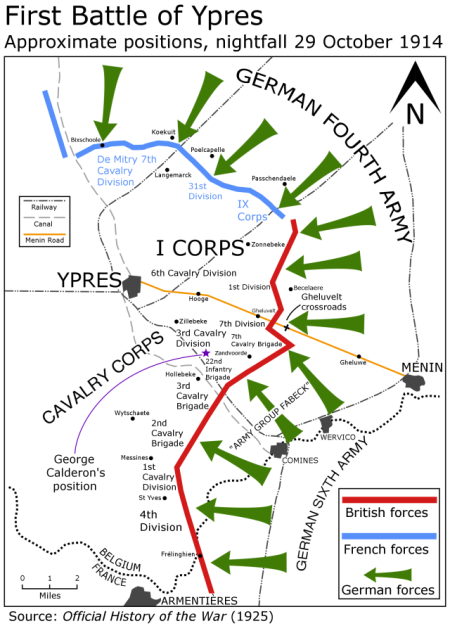

Today, Saturday 31 October 1914, George Calderon was presumably travelling in a hospital train to one of the Channel ports. The day is a black hole in his biography, but as Kittie remembered it he arrived in London on 1 November.

It is an unspeakable relief to be off the battlefield. I have been submerged in histories, studies, maps, diaries of the war, since the end of July. The disadvantage of the timeline approach I chose for this blog is that I have come to ‘live’ the war and George’s experience of it, day by day. And it has ‘got’ to me. The massed slaughter and mutilation, the material destruction, the relentless stupidity of it all, begin to depress you, then oppress you. Come last weekend, when we were working on the Battle of Gheluvelt, I literally wanted to shout with Siegfried Sassoon, ‘O Jesus, make it stop!’

Then reading and re-reading Calderon’s letters day by day has revealed things about him that I did not know, and certainly was not expecting to discover this late in writing his biography. Of course, as a 45-year-old writer/scholar completely unused to military action, he was under great stress; one should not underestimate that. Within a week of arriving in Belgium he was also displaying a potentially life-threatening medical symptom. Even so, some of the aspects of his character revealed here are challenging.

An historian said to me, ‘I find Laurence Binyon’s war effort far more impressive. Instead of prancing about on a horse like Calderon, he went and washed floors and attended the wounded in a military hospital.’ Indeed, there does seem to be an element of exhibitionism in all George’s military doings since arriving on Salisbury Plain, especially in his hyperactivity 27-29 October. The other officers may have regarded his unilateral efforts to catch snipers as a liability, and himself as a ‘plonker’ when he got shot. As he was being stretchered out of the field ambulance on the night of 29 October, he heard a wounded officer inquire whether it was ‘that cheery cove’. George quotes this as a compliment, but I’m not so sure. What is one to make of his claim (29 October) that interpreting work was ‘too hard’, when he had repeatedly told Kittie he had nothing to do?

Again, we should not forget the stress Calderon was under. But there is more evidence in these letters from Belgium that he was bipolar than anywhere else in the biographical material. I am inclined to think that Kittie suppressed letters both from Belgium and before in which George was specific about his depression. On two occasions, 1904 and 1906, he certainly suffered from acute ‘nervous exhaustion’.

Perhaps the biggest surprise, however, is the nastiness of some of his language. It occasionally takes a homicidal turn (‘let him be hanged on a high gallows in Whitehall’). In Calderon’s fiction, for example Dwala, one reads this as satiric anger. There is no evidence of intemperate, corrosive language in any other personal letters of his that have survived. However, perceived nastiness was precisely what people did not like about George in the Stage Society and in the anti-suffrage movement — that is well documented.

In my post on 28 October I did not have room to quote a long paragraph in his letter of that day, describing a search that he initiated and led of a neighbouring farmhouse where the peasants were hanging up tobacco in an outhouse. He had become ‘d—–d suspicious about these poor suffering Belges’ in general, and had ‘a telepathic suspicion’ about these ‘nasty shady-looking’ peasants in particular. He believed that a lot of the sniping came from the Flemings themselves. He did not find anything at the farmhouse, but was evidently pleased that they were ‘devilish frightened at my visiting the tobacco shed’. ‘They’re an ignorant selfish boorish crew, all over here’, he told Kittie.

It is tempting to think that Calderon had become paranoid, but as he said earlier ‘nobody in the British army trusts them [the Flemings] an inch’. Some of the local peasants were arrested for spying, but it sounds to me that the suspicion of them sniping at British troops is of a piece with the Germans’ obsession with ‘francs tireurs’, which led them to commit mass executions of civilians in France and Belgium. I do not know that any historian has got to the bottom of whether such snipers ever existed.

Many of George’s actions and pronouncements at the Front I find exasperating. Certainly I can see the historian’s point about comparing him with Binyon. In a word, was Calderon just ‘pissing about’ as a soldier?

It may look like this at times, but I would refer you back to my post of 18 September. The one consistent and impressive thing about the whole period 8-30 October is his writing. As a follower emailed me a few days ago, it is almost incredible how often and how much he wrote to Kittie (and remember that there were other letters, now lost). This could not have been easy. Ranks watching him, and the censor, must have realised he was a professional writer. Towards the end, he was so stressed that he repeated himself in the same sentence and misspelt words, both of which are almost unheard of in him. But he kept writing, and there is plenty of wit, elegance and vivid observation in his letters. You feel in places that he is writing for the record. I have no doubt that if he had come through the war he would have used the letters to write a book.

In his TLS blog post Michael Caines described George as ‘complex, versatile and restless’. One is used to Edwardians being versatile, restless, amateur, or dilettante, say, but complex? It was very perceptive of Caines, after (presumably) a relatively short acquaintance with George, to conclude this. ‘Did one human body ever hold quite so simple yet quite so complex a soul?’, wrote Kittie in her memoirs.

His complexity is a function of his genius.

Next entry: 1 November 1914

Zillebeke Churchyard Cemetery

This week I have received and read Jerry Murland’s 2010 book Aristocrats Go to War: Uncovering the Zillebeke Churchyard Cemetery. Nothing, I think, could evoke so strongly the character and ethos of the men George Calderon was with at Ypres in 1914. It is a gripping read, 180+ pages long, very well illustrated, and written by an ex-Parachute Regiment soldier who knows about war. I warmly recommend it.

Unsurprisingly, George doesn’t appear in it, but the interpreter who took over from him after 15 October, the twenty-seven-year-old Baron Alexis de Gunzburg, does. He was called down to Windmill Hill Camp in September like George, but promptly sent back to London to get himself naturalised, as it was discovered he wasn’t a British subject! Fast-tracking his naturalisation wasn’t difficult given his family’s connections, which included Winston Churchill, who was also Colonel Gordon Wilson’s nephew by marriage…

Very appositely, for my purposes, Murland describes Gunzburg thus:

I also understand now, from Murland’s copious references to Colonel Wilson, why George admired/loved the man so much. He was clearly an exemplary and charismatic Edwardian officer-gentleman of the ‘old’ professional army. Not only had he helped foil an assassination attempt on Queen Victoria when he was still a sixteen-year-old Etonian, won the Grand National in 1892, and been A.D.C. to Baden-Powell throughout the Siege of Mafeking, he was, in Murland’s words, a ‘strategically able, good cavalry commander and first-class manager of men and resources’. It is a compliment to George, then, that Wilson originally chose him as his Interpreter.

Wilson and Gunzburg are buried with sixteen of their comrades in the cemetery at Zillebeke, a mile or so from where they were killed on 6 November and only a couple of miles from where I think George Calderon was wounded.

Today, 15 November 1914, the first snow fell in Flanders.

Next entry: Nuts and bolts