The other evening, I met a friend at a party who told me she had recently taken part in a reading of George’s ‘Romantic Comedy in One Act’, The Maharani of Arakan. I was amazed, as I had not heard of any presentation of the play since 1916. However, my friend thought it may often be performed by Indian cultural societies — and this appears to be borne out by the number of different print on demand editions available through Amazon, AbeBooks etc. She herself has long been involved with Indian culture and religion, and the reason she recommended the play to her reading group was that it is based on a story by Rabindranath Tagore (I don’t think she had previously heard of George).

Her news gave me an uncomfortable jolt: I had completed chapter 14 (1914-15) in February without mentioning the publication of The Maharani of Arakan in 1915! Admittedly I had discussed the play in chapter 13, ‘Wilder Shores of Translation’, in the context of George’s less conventional ‘translations’ (he did not know Bengali, Tagore’s original story was written in English, yet Tagore himself referred to George’s adaptation as a ‘translation in the form of a drama’); also in the context of the Edwardians’ reaching out to eastern cultures, and the visit by Tagore to London in 1912 organised by William Rothenstein and others, for which George had made his dramatisation (it was performed at the Albert Hall in Tagore’s presence on 30 July). But on the face of it, The Maharani was George’s only publication in 1915 and the last within his lifetime, so surely I should have mentioned it?

Not only that, if it came out in 1915 George might have been working on it during his ‘Friday-to-Monday’ leave, along with Tahiti and The Lamp, so it ought to have featured on this blog long ago?

The only trouble with that line of reasoning is that there is no mention in the whole of George and Kittie’s correspondence of 1914-15 that he is working on the text for this publication, reading proofs, expecting its appearance in print, and so on. Of course, we don’t, mysteriously, have any letters from George at Fort Brockhurst to Kittie between his arrival there in mid-January and his embarkation for Gallipoli on 10 May, so there could have been mentions of The Maharani in the missing letters. Even so, one might have expected passing mentions in his letters from 10 May onwards, or in Kittie’s memoirs. Could The Maharani have been published after his death?

The encounter with my friend sent me back to the ‘Tagore file’. The deeper I went into it, and the more I searched the Web, the more mysterious the whole business of this play’s performances and publication became.

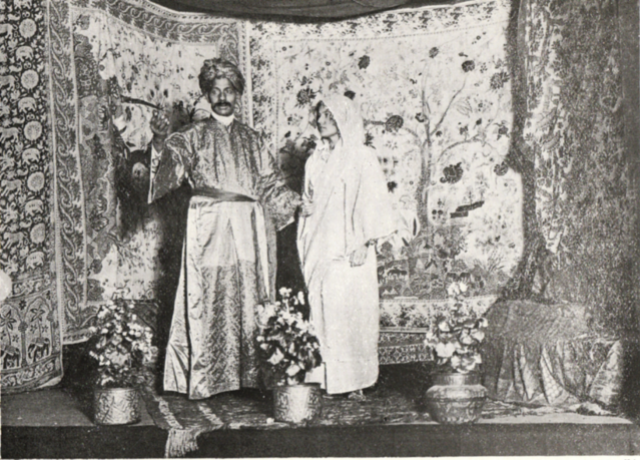

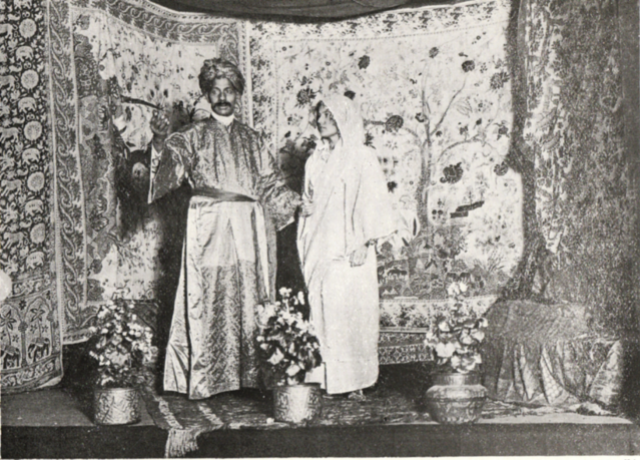

I have a rare copy of the first edition, bought through AbeBooks some years ago, and I discover that it belonged to Ronald Colman, the future Hollywood heart-throb, who played Rahmat Sheikh in the 1916 production at the Coliseum and dated his copy ‘June 1916’. In this edition, there are numerous photographs and sketches by Clarissa Miles (no relation). The photographs show K.N. Das Gupta and Margaret Mitchell in the lead parts of King Dalia and Princess Amina:

K.N. Das Gupta and Margaret Mitchell in an Indian Art and Dramatic Society production of The Maharani of Arakan, 1913/14?

One might assume these photographs were of the 1912 premiere at the Albert Hall, but no — reviews reveal the cast was entirely different! Obviously they could not be of the 1916 production, as the book, we are told on the title page, was published in 1915, and in any case the cast at the Coliseum, where it ran for a week from 19 June 1916, was different again. We know from a letter to George written by the composer Albert Cazabon on 29 October 1913, regarding the Bengali music for a production, that for that production Cazabon’s own wife, Gladys Curtin, was to play Amina, so presumably the photographs in the published playtext were not of that production, either. What is going on?

It seems a reasonable hypothesis that for the public performances at such grand theatrical venues the producers would want the strongest actors they could get and these would have to be professionals. There were professional British actors, e.g. Sybil Thorndike, associated with the Indian Art and Dramatic Society, but it seems likely that the Society’s own in-house productions would have had amateur actors. K.N. Das Gupta, for example, who looks splendidly authentic in the published photographs, was not a professional actor. Margaret Mitchell looks as though she could have been, but the others do not. Suggestions in various Web articles that K.N. Das Gupta and Sybil Thorndike acted in the 1912/1916 productions are demonstrably untrue.

The simple hypothesis from all this is that there was an original Indian Art and Dramatic Society production before the 1912 Albert Hall performance, and another in 1913/14 before the 1916 Coliseum one (i.e. the one referred to by Cazabon in his letter to George). Presumably Das Gupta and Mitchell played the leads in one or both of these, from which the photographs for the 1915 publication were taken.

I incline to the idea that the photographs were taken nearer to the publication, i.e. in 1913/14, than before the Albert Hall performance. The Society had been in existence only seven months before the latter. Isn’t it more likely that as soon as they knew Tagore was visiting London, George made his dramatisation and the professional theatre people in the society went straight into preparing a production for the Albert Hall?

I also think that the key to the photographs in the published version (which stresses at the front that the play was ‘Staged by the INDIAN ART AND DRAMATIC SOCIETY’) is the ‘irrepressible Das Gupta’, as Rothenstein described him to Tagore in a letter of 1913. Das Gupta was a seamless blend of cultural and commercial entrepreneur. He had founded the Society (later to become the Union of the East and West), was its driving force, and the 1915 publication was evidently his project (Clarissa Miles was the Society’s secretary). Despite its cover and spine declaring it was The Maharani of Arakan by George Calderon, it was more of a celebration of Tagore and Das Gupta. It opened with a twenty-two page ‘Character Sketch of Sir Rabindranath Tagore, Compiled by K.N. Das Gupta’ but actually written by other people including W.B. Yeats. Then followed the play, covering thirty-two pages, then three pages of music to the songs and one of reviews of the Albert Hall production. The play was preceded by a note referring to the publisher for performance rights, and three out of the five photographs featured K.N. Das Gupta.

I submit that the publication was a commercial venture of Das Gupta’s in anticipation of a full professional production. In such circumstances — as today — the play text was published to just precede or coincide with the production. The TLS reviewed it on 16 March 1916. Usually, the TLS reviewed books within a week or two of their publication. A gift copy of the book that I have seen is dated ‘Easter 1916’, which was 23 April. A review of the 1916 production dated 20 June speaks of George’s play having been ‘lately published in book form’, which could hardly refer to the year before.

My presumption is that K.N. Das Gupta had the book printed in 1915, but only brought it onto the market when the Coliseum production was assured in early spring 1916. It was great publicity for the production, the Society, and himself as entrepreneur, impresario and actor. He used the final acting text of 1912, so George had no need to work on it in 1914 or 1915 and therefore never mentions it in those years. If this scenario is correct, George never saw the published result.

Next entry: 10 April 1915: A professional soldier

25 April 1915: The bloodbath begins

At 4.30 this morning the first ANZAC troops began landing at Z Beach on the Gallipoli Peninsula. They were not strongly opposed, as von Sanders’s strategy was to keep a light screen around the coast until it was clear where the Allied landings actually were, then feed in his central reserves. Through the day, the landings and the advance at Z Beach became more and more chaotic and the Turkish defence ever fiercer. By nightfall the situation for the Anzacs was critical. Their commander, General Birdwood, even contemplated taking the force off again. Hamilton, however, told him there was ‘nothing for it but to dig yourselves right in and stick it out’. The landing had been a failure and the Anzacs were confined to an incredibly narrow bridgehead for the next eight months.

At Y Beach the 1st King’s Own Scottish Borderers (to whom George would eventually be attached) scaled sheer cliffs in the semi-dark and at first met no resistance. However, they did not dig in, nor did they advance until the afternoon. It was then a similar story to Z Beach. They became desperate for reinforcements, which did not arrive, and ‘all night the Turks pressed hard all along the overstretched line’ (Peter Hart).

At X Beach the naval support was highly effective, the Royal Fusiliers pushed on to their objective, which they had captured by noon, but they were forced almost back to the cliffs by a Turkish counter-attack in the afternoon.

At W Beach, the Turkish defences had not been effectively shelled by the navy and the Lancashire Fusiliers were mown down as they came ashore or lay by the wire waiting for it to be cut. The situation was saved by an outflanking attack, but even so Turkish reinforcements prevented the British troops from achieving their objective of joining up with the main landing force at V Beach.

It was at V Beach that the biggest disaster occurred. This was the most strongly defended point at Cape Helles. As the River Clyde, containing two thousand men, grounded to the left of Sedd el Bahr Fort just after 6.00 a.m., followed by open rowing boats containing the Dublin Fusiliers, a storm of fire broke out from the castle and Turkish trenches. The first assault force was practically shot to pieces or drowned before reaching land. The landings from the ‘Trojan Horse’ of the Clyde had not been thought out or rehearsed in detail and turned into fiasco and mass slaughter. The sea was red with blood. Two platoons were successfully landed to the right of the castle, advanced on the village, but were beaten back. The landing force suffered about 1000 casualties in the course of the morning and the attempt to disembark the rest was called off until nightfall.

The map tells a terrible story of failure. It had been thought a reasonable objective to join up the forces at Y, X, W, V and S Beaches and take the commanding height of Achi Baba, five and a half miles from Helles, on the first day. The Expeditionary Force never reached Achi Baba or Mal Tepe in the entire course of the campaign.

(Figure from the official history, Crown Copyright 1928)

As with my post yesterday, I feel the less I comment on the Gallipoli campaign the better. No-one, probably, has put it better than Nigel Steel, Principal Historian for the Imperial War Museums, in his interview ‘Gallipoli Dissected: What Did Britain Get Wrong?’ at http://www.historyanswers.co.uk, and Peter Hart in Gallipoli (Profile Books, 2013).

My biography of George Calderon has grown into an examination of the Edwardian ethos or mindset. I will merely say, then, that for me the Gallipoli campaign exemplifies the very worst about the Edwardians (naive over-confidence and arrogance) and something of the best (individualism and courage).

Next entry: 26 April 1915