In my 22 January post I explained the meaning of the Edwardian verb ‘to apple’. I mentioned that five lines in George’s letter to Kittie of 10 May 1915 were ‘appled out’ and I was following up ‘forensic programmes’ for reading beneath crossings-out.

Unfortunately, consultation with a retired Chief Constable revealed that the police don’t have such ‘forensic programmes’. They too are dependent on magnifying glasses, lighting, Ultra-Violet lamps, digitalised imagery and traditional methods of deciphering handwriting. Since January, then, I have tried all that, with the help of my own computer and of UV equipment belonging to the Manuscripts Department of a local museum.

The most productive method has been the ‘traditional’ one: constructing on paper a grid of the lines of writing and the separations between words (as far as one could ascertain these spaces), then trying to read George’s writing beneath Kittie’s ‘appling’ at irregular time intervals, with a magnifying glass, and with lighting of different intensities at different angles, then transferring what one could make out to the grid. It is surprising how differently one sees the appled out writing each time one comes to it afresh.

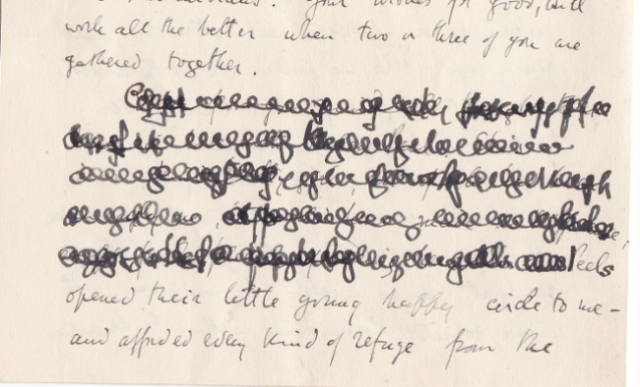

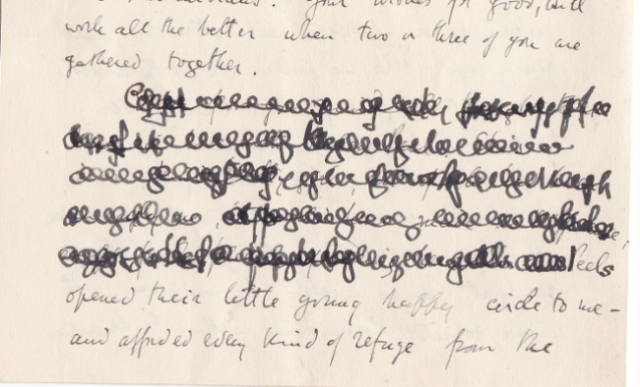

Even so, because George’s pen is very fine and his ink faded, this is all that to date we have been able to identify:

The original five appled lines

What we have so far

If anyone can decipher more, or has any suggestions about how we might tackle the problem further, please say so in a Comment asap!

In my January post I wrote that the ‘appling’ in George and Kittie’s letters raises the question of breaching their privacy — as it were their ‘trust’ in me as their biographer. Everyone who has discussed this with me in the case of this letter has said they think we should attempt to de-apple these lines. But that might be just because they are nosy!

My own view is not Aubreyan. I don’t believe the biographer’s job is at all costs to seek out the sensational and salacious, which Aubrey erroneously called ‘the naked and plain truth […] exposed so bare that the very pudenda are not covered’. Such ‘naked and plain truths’, which are actually just facts, may not be typical, or at all important in the big biographical picture. To focus on them might just be prurient.

I believe it is a question of perspective. Admittedly, this is itself a very personal matter. For instance, it was very important to Percy Lubbock, writing George Calderon: A Sketch from Memory for Kittie in 1920, to focus on George’s war experiences and letters from the two fronts; so much so that they make up a fifth of his book. I devote only a tenth to George’s year as a soldier, because my perspective is more holistic or, to be honest, skewed towards George’s writing, thinking and activism in the rest of his life. In that context, a few lines appled out here (before the letter was shown to George’s first biographer, Lubbock), or in George’s love letters to Kittie (which Lubbock did not see at all), may not be very significant — although I agree that the biographer has got to know what is appled out before he/she can decide how significant it is.

Finally, you of course must discuss such issues with the descendants of those people who feature in your biography. You are not a tabloid journalist. The living descendants will have sensitivities and a view of their own, which you must respect. I am delighted to say that in the case of key players in George Calderon: Edwardian Genius, their descendants and I are in absolute agreement. On the one hand, ‘a hundred years is a long time passed’, as one expressed it to me; on the other, what one is after is a true perspective.

Today the Battle of Festubert was launched on the Western Front between Neuve Chapelle and La Bassée. It was the first British attempt at attrition and about 100,000 shells were fired in the first sixty hours. The front wavered back and forth for the next ten days. British casualties were 16,700, German approximately 5000. By the end of the offensive the line had advanced two miles and British forces were completely out of shells.

Next entry: 16 May 1915

‘New Western Polovtsians’

The 1st KOSB had had a disastrous start at Y Beach on 26 April (see my post for that day), but had since become part of the very backbone of the 29th Division at Helles. In this letter George also tells us that he is in B Company, commanded by Captain Grogan (aged 25) of the 9th Ox and Bucks. George was a subaltern commanding one of the four platoons in this company.

The very long third sentence of the first paragraph, and the references to the enemy as ‘Him’, again mirror Tolstoy’s Sebastopol stories that George had been reading in Russian on the voyage.

For obvious reasons, George does not mention the sinking of the battleship H.M.S. Majestic off Cape Helles at 6.40 this morning by the German submarine U-21, although he must have witnessed the rescue of its crew.

The ‘big moleheap’ in the distance is Achi Baba, which the Allies had been trying to reach since 25 April.

The idea that the Turks were about to be ‘swallowed’ by ‘the tip-end of a big civilisation’ is either a joke on George’s part or a gross self-deception. The Polovtsians, a nomadic East Turkic people, were the heroes of ‘Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor‘, the ballet choreographed by George’s friend Fokine and first presented in London by Ballets Russes on 21 June 1911.

‘Tommy’ is George and Kittie’s mongrel dog, whom he exercised on Hampstead Heath.