Of course the Adjutant turned him down – saying he was far too old.

It must have been a bitter blow to Calderon, yet it is very unlikely that he showed it. He may have tried to reason, perhaps he employed some of his inimitable humour and charm, but in the words of a friend he always displayed ‘truly Spanish courtesy’, so he probably appeared to accept the Adjutant’s rejection.

He was not the only man being refused. In Manchester the Guardian’s theatre critic C.E. Montague, who had reviewed George’s play Revolt so perceptively and at such length in 1912, tried twice to enlist at the age of 47 and succeeded only after dyeing his white hair black, prompting a colleague to remark that ‘Montague is the only man I know whose white hair in a single night turned dark through courage’. There may well have been other over-age ex-barristers trying to join the colours on that station platform as the Inns of Court Regiment entrained for Camp.

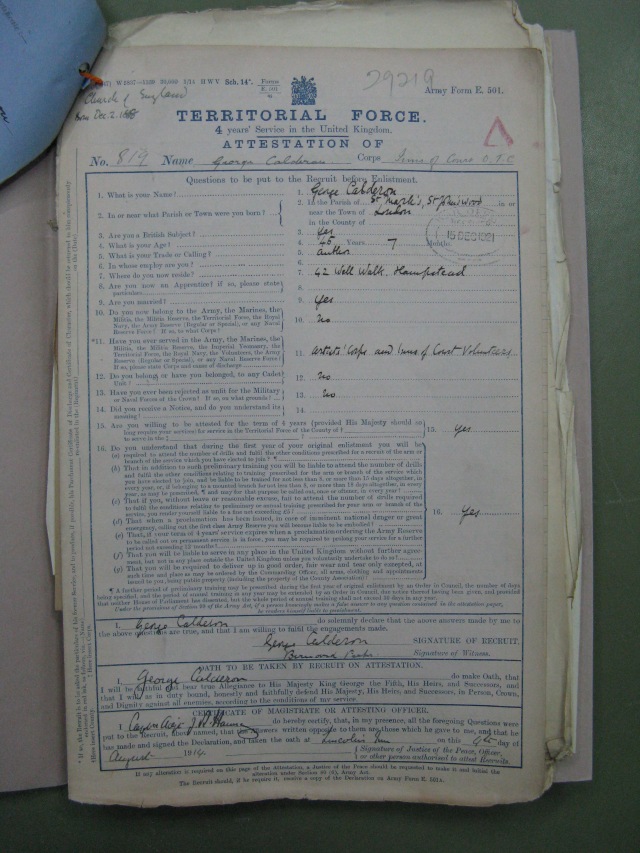

Rejecting Calderon was a mistake. The afternoon before, Germany had invaded Luxembourg and was demanding unhindered passage through Belgium, obviously to attack France. George Calderon was a man who spoke ten European languages, loved sport, had five years military training in his past, and was fearless. Moreover, as his interventions in the Coal Strike and London Dock Strike of 1912 had shown, he had a ‘propensity to act’ that left most people standing. But he was ‘too old’…

Wearing the uniform he and Kittie had improvised, he returned to Hampstead, where the annual Cockney Carnival was in progress (it was August Bank Holiday, a ‘St Lubbock’s Day’). But according to the local paper, this was ‘a dismal affair […] the true holiday spirit as only was to be expected was absent’. Mobilisation orders were now being sent out. That afternoon, Sir Edward Grey addressed the House of Commons on what he saw as the country’s moral obligations. Bank Holiday crowds gathered in Whitehall and outside Buckingham Palace. Back at the Foreign Office, Grey worked on the ultimatum to Germany demanding it respect Belgium’s neutrality, and this evening a hundred years ago Germany declared war on France.

In Hampstead, George Calderon was conferring with military friends and planning his own campaign for the following day.

Next Entry: 4 August 1914

A biographer writes…

The main object of ‘Calderonia’ is to post events and documents in a kind of ‘real time’ ; exactly a hundred years after they happened. And judging by the emails I have received, that’s what people appreciate. This timeline approach is a great help to me as I piece together the narrative of the last chapter of my biography of Calderon (not the last chapter of the book), which I shall start writing next week. I also know that I can go into more detail, and quote far more, in the blog than I’ll be able to in the chapter.

Unfortunately, although probably more is known about the last ten months of Calderon’s life than any period of similar length, we don’t know something specific or have a document about every day of it. In those gaps, then, I shall post personal commentary on odd days. Sorry if this isn’t as interesting! But, of course, I’m always keen to get your comments and reactions back. The next actual document, a letter of Calderon’s to his mother, will be posted on 14 August and is, I think you’ll agree, a gem.

Next Entry: A biographer dreads…