Foxwold, by James W. Herald, c.1894

Christmas Day 1914 was a Friday. Two days before, George and Kittie Calderon, together with their Belgian refugees Jean Ryckaert and Raymond Dereume, made their way by train to Sevenoaks, where they changed for Brasted. At Brasted station they were collected by pony and trap, most probably, and taken to the rather grand, but architecturally eccentric country house Foxwold (see parts of the 1985 Merchant Ivory film A Room with a View). They returned to Hampstead on New Year’s Eve and on 1 January 1915 George wrote a cracking letter to William Rothenstein which will form my next posting.

Foxwold, which was owned by the thirty-five-year-old Captain C.E. Pym (‘Evey’), provided the perfect family Christmas for the Calderons. They adored his thirty-two-year-old wife Violet (‘Wiley’), her soldierly husband, and their three small children, who have featured in ‘Calderonia’ ever since my first posting on 30 July. Other Pym family members were there for Christmas, too. Just up the road was Violet’s parents’ home, Emmetts (see www.nationaltrust.org.uk/emmetts), which also had a full house this Christmas, and festivities were shared between the two houses.

The family connection between the Pyms and the Calderons was that Violet’s mother, Catherine Lubbock, née Gurney, was the half-sister of Kittie’s first husband, Archie Ripley (1866-98), who had been a close friend of George’s from their Oxford days. The Lubbocks were a large and famous family, a national treasure indeed. Violet was Catherine and Frederic’s only daughter. Her brothers were Guy, Cecil, Samuel, Percy, Roy and Alan, at least four of whom were present at this Foxwold-Emmetts Christmas.

One feels that Christmas at Foxwold must have been English and Dickensian par excellence. Evey Pym was frugal, but his father Horace, for whom Foxwold was built in 1885 , had famously entertained there, was a very successful Victorian ‘confidential solicitor’, a bibliophile, raconteur, and great admirer of Charles Dickens (whose sister-in-law Georgina Hogarth stayed at Foxwold for ten days in 1896). Surely something of Horace’s expansive conviviality rubbed off on the way his son kept Christmas in 1914?

The presence of children was vital to the festivities and to George and Kittie’s enjoyment. George was a master at organising games and charades, and according to Percy Lubbock he taught Ryckaert and Dereume to ‘build a toy theatre’ — presumably in order to stage a performance on it for the children. The construction probably took place in the largest room at Foxwold, Horace Pym’s L-shaped library. George painted the proscenium and Evey the Royal Arms at the top:

Toy theatre proscenium by George Calderon and C.E. Pym, Christmas 1914

Calderon was ‘at his kindest and sunniest’, Percy Lubbock recalled: ‘What I see is his whimsical, interested face as he describes the delight of searching a ruinous farm-house in the dark, where a German sniper is concealed.’ He coached the Belgians in billiards and even ‘acted polyglot charades with them’. At Ypres on Christmas Day some of George’s former regiment, the Warwickshires, met their enemies in no man’s land.

On 27th there was a heavy fall of snow across Britain.

It was presumably at this point that, in Kittie’s words, ‘one of those glorified charades that George was so splendid at evolving was got up for the soldiers quartered in the village’. It was performed in the village hall. Unfortunately, we have no evidence that George acted in it himself as he had in his uproarious ‘Ibsen Pantomime’ at Emmetts in the festive season of 1911/12. ‘It was extraordinarily funny and clever’, Kittie wrote, and George ‘thoroughly, as usual, enjoyed his time at Foxwold’.

But, of course, the war was at the back of everyone’s minds. Percy Lubbock wrote in 1921:

That Christmas party had travelled far in a few months […] I seem to remember a frame of mind in which two firm convictions dwelt side by side — that the war must certainly end within a few months more, and that it would somehow not end after all; it was impossible to suppose that it would last, it was unimaginable that it should cease. But George himself was little concerned with this dilemma; he looked neither backward nor forward, he had work on hand that made the moment all-sufficient. He was a soldier in the war, slightly damaged for the time being, but well enough to be planning his return to activity […] I think of him as the one member of the party who seemed to live serenely in the midst of the upheaval, on sure foundations that he could trust. All around him were trying, more or less successfully, to adjust their balance to the new conditions; he, from the first moment of the war, was firmly on his feet, and never had to think of the matter again. […] He was one of the few whom the war found ready, morally and intellectually; he had no further preparations to make.

Kittie Calderon saw only the rehearsals for George’s show at Brasted village hall; she was not well enough to attend the performance. She had, in fact, not been well for some time. One would give a lot to know what her mystery illness was, but one can imagine some factors that influenced it.

All the images illustrating posts connected with Foxwold, and a huge amount of the information these posts contain, have been supplied with unstinting kindness and generosity by the descendants of Violet and Evey today. I am sure that followers of ‘Calderonia’ will want to join me in wishing the Pym family the most Dickensian of cheer this Christmas, one hundred years later and in happier times.

Next entry: 1 January 1915

A review

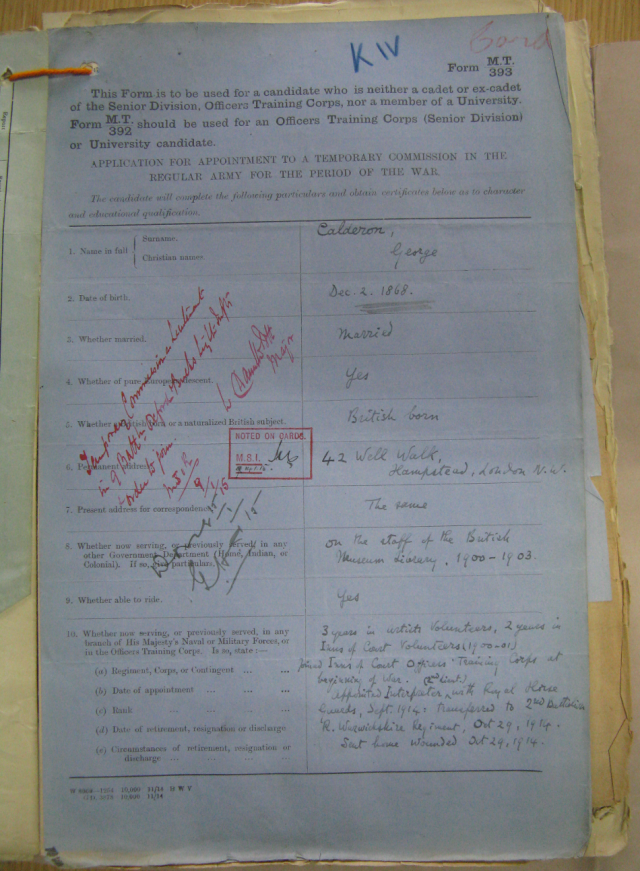

George’s commission was dated 9 January 1915, which was a Saturday, and on the same day the literary magazine The Athenaeum came out with an unsigned review of his translation of Il’ia Tolstoi’s Reminiscences of Tolstoy. However, it is likely that George received notification of his commission long before he read this review, as he was not a fan of The Athenaeum and probably waited for the publishers of his translation, Chapman & Hall, to send him a copy from their cuttings agency.

The curious thing about this review is that it was appearing nearly three months after the book was published — and in those days book reviews tended to come out far closer to publication date than they do today. As I explained in my post of 5 November, for George Calderon to net the job of translating Tolstoy’s son’s ‘sensational’, eagerly awaited memoirs was a tremendous endorsement of his status as a Russianist and writer of English. His translation was serialised for four months before book-publication on both sides of the Atlantic, but probably the War took the edge off its reception.

The most likely author of the review of 9 January 1915 was the English Tolstoyan Aylmer Maude (1858-1938), and his nose was probably put out of joint by George getting the contract to translate the memoirs in the first place. One of the reasons Maude was not chosen as translator was probably to do with Tolstoy family politics following Lev Tolstoy’s death in 1910 (Aylmer and his wife Louise had been deeply enmeshed with the family whilst Tolstoy was alive, whereas George had never been).

I won’t ‘go on’ about George’s and Aylmer Maude’s relationship, but I will say that it was quite complex. As someone who had taken Tolstoy’s ‘philosophy’ apart in an article of 1901 more comprehensively than anyone before George Orwell in 1947, Calderon was unlikely to have much in common with a man who believed in this ‘philosophy’ and had even tried to live it in a fissiparous English commune. Maude’s close involvement with Fabianism and his admiration of G.B. Shaw would also have been anathema to Calderon. The latter’s main differences with Maude were, however, probably literary.

A major reason for suspecting that this review was written by Maude is stylistic. The author swiftly sidesteps the unique quality of these memoirs — their intimate domestic portrait of Tolstoy, their interpersonal emotional depth — in favour of (a) discussing ‘the omission of many things which loomed large in Tolstoy’s career’, and (b) expatiating ad nauseam on ‘the very few slips we have noticed in the book’, e.g. minutiae connected with Tolstoi and chess, which Maude himself had played with the writer. This is very reminiscent of George’s criticism in the TLS (11 March 1909) of the first volume of Maude’s own, authorised biography of Tolstoy:

In other words, Maude was a ‘compiler’… A severe warning, this, from George to biographers everywhere!

Just as, in his review, Maude does not seem to grasp the deeply empathic nature of Il’ia Tolstoi’s memories of his father, and how wonderfully human, warm, unpretentious and playful the Tolstoy of these Reminiscences is, so too Maude’s response to George’s translation is limited to the ineffably pedestrian ‘Mr Calderon’s English version is fluent’. As Vladimir Nabokov pointed out long ago, in translation ‘fluency’ and ‘readability’ may be the last refuge of a scoundrel. George’s version, in fact, is not ‘fluent’ in the sense of ‘plangent’, or of water running out of a drainpipe; it is alive, individual, and full of interesting English surprises.

The fact of the matter is, Maude and many other Edwardian Russia-fanciers, e.g. Maurice Baring and Constance Garnett, were good linguists but neither literary nor critical, which George Calderon was.

Nevertheless, at the end of his (?) review Maude conceded: ‘the big thing is that we are indebted to Mr Calderon for presenting this book to us in a form in which it can be read with pleasure’. This is very reminiscent of the compliment George paid to Maude in his TLS review (6 October 1901) of the second volume of Maude’s biography of Tolstoy: he said he was ‘a man of a rare sort, himself an idealist, a seeker, an experimenter, of keen intelligence, devoted to public good’.

The mutual respect between two such different Russianists and men must have been an advantage when in 1913 Maude moved into lodgings with Marie Stopes and her first husband a hundred and fifty yards away at 14 Well Walk and Calderon and Maude occasionally passed in the street.

If anyone out there knows for certain who the author of this review was, will you please tell us in a Comment?

Next entry: The military situation