I have just read a long article by Ruth Scurr, ‘Lives, some briefer than others’, in last Saturday’s Guardian Review (28 February), which I thoroughly recommend to followers if they can get it, along with a piece by Stuart Kelly, ‘Enter John Aubrey’, which can be accessed through the TLS Blog link on the right (go to ‘More recent pieces from the TLS’). Both articles arise from the imminent publication of Ruth Scurr’s ‘biography’ of Aubrey, John Aubrey: My Own Life.

I may have missed something, but it seems to me that Scurr’s essay is the most wide-ranging and stimulating contribution to the subject of modern biography to have appeared in the British press since a piece by Michael Holroyd about ten years ago. As Scurr says, ‘biography is an art form open to constant experiment’; to stay alive, it has to keep reinventing itself. Holroyd’s view, as I remember it, was that biography had to move closer to the novel and that’s what readers wanted. At the time, I was actually contemplating a novel about George and Kittie Calderon entitled Golden Square. This was because although I had access to all their extant papers, there was still a huge amount I would have to imagine, wanted to imagine, and I thought their story more ‘human’ than ‘biographical’. As more and more documentary evidence emerged, however, the balance in my mind shifted. Even so, in the past seven months two followers of this blog, perhaps beguiled by the runs of days when I can tell the Calderons’ story in ‘real time’, have asked me whether I have ever thought of writing such a novel.

Scurr’s essay is positively inspiring, at least to this biographer, because it touches on one vibrant issue of biography after another; issues that whizz around in your head as a practising biographer but perhaps have ne’er been so well expressed. I can’t address many today, but here are a few.

‘Novelists can write what they want to happen,’ Scurr says, ‘but biographers must write what actually happened.’ This may seem trite, but it isn’t. ‘All biography is fiction,’ Donald Rayfield wrote of his monumental life of Chekhov. I found this a worrying thought as I read it, but literarily, formalistically, it’s indisputable (he added: ‘but fiction that has to fit the documented facts’). As I have said in this blog several times, I try to write George’s life ‘in real time’ as though it is happening, which for stretches perhaps brings it close to a novel, a work of fiction. I rejected footnotes for that very reason. But of course everything in it still has to be evidenced from the past. It is all too easy to forget that. For instance, it was an informed guess that George moved back to Brockhurst on 3 March 1915, it is speculation that whilst he was convalescing he worked on the synopsis of Tahiti that would enable Kittie to publish the book if he didn’t return from the war, and it is pure speculation that he did nothing after 4 August 1914 about finding a producer for The Brave Little Tailor. Those are examples from just the last week’s posts! How right Scurr is to remind us of Defoe’s warning against ‘a sort of lying that makes a great hole in the heart at which, by degrees, the habit of lying enters in’ — in other words, against appropriating your subject’s life so much that it becomes fiction. The chance discovery some months ago of a pocket diary of George’s for 1907 completely blew away several assumptions about events in his life that I had already written into my biography of him.

It is because readers do want ‘the true facts’ of a person’s life, whether out of sheer curiosity or for extraneous purposes, that there will always be a demand for the ‘traditional’, ‘linear’, ‘boring’ biography. And what is wrong with that? It still has to be written well enough for the reader to want to turn the pages. But I have to say that for me these words of Scurr’s come closer to home: ‘The fundamental problem is always the same: how to find a narrative form that fits the life (or lives) in question.’ Personally, I found the narrative form of George Calderon: Edwardian Genius through what I call, quoting a poem of Graves, the ‘tourbillions of Time’ in Calderon’s relatively short life. If ‘editors’ aren’t going to like the fact that there are two more chapters after George’s disappearance at Gallipoli, they are going to like even less that he hardly features in the first chapter, that his story starts in 1898, flashes back to Russia 1895-7, then 1868-95, then returns to 1897-1906, then there is a set of chapters that are really thematic (synchronic), then the last three are purely linear (diachronic)…

Here are some more warning words of Scurr’s that I agree with: ‘Like scholars who have “mastered” a particular topic or archive, the biographer can come to feel he or she owns their subject.’ As I said in my post about the American biographer Park Honan (21 December 2014), I believe biography is an act of intense empathy, but you have to come out of the other’s self again to write the biography. Further, ‘if there is no such thing as a definitive biography,’ writes Scurr, ‘there might at least be a groundbreaking one, offering something that has never been seen or heard before. It is in the hope of thwarting such life-hunters that people resort to burning letters and journals.’ Oh dear, there is certainly a suspicion in my mind that that is why Kittie willed so many of her letters and George’s papers to be burned. Perhaps she intended Percy Lubbock’s 1921 George Calderon: A Sketch from Memory to be ‘definitive’, literally the last word?

Inevitably, one will not agree with everything Scurr says. She begins by talking of Aubrey’s ‘child’ being ‘the publishing phenomenon of our time’ and suggests it is outselling history in the bookshops. But this is true only sensu lato. To claim it, she elasticates ‘biography’ to include autobiography, memoir, celebrity stories and ‘innovative books such as Helen Macdonald’s H Is for Hawk‘. Nothing in this world or the next, I believe Eliot said, is a substitute for anything else. ‘Biography’ is a genre — ‘traditional’, ‘starting at the beginning’, ‘linear’, ‘boring’ — and autobiography, memoir, celebrity stories, faction, are other genres of their own. The challenge is to develop and deepen the genre ‘biography’, possibly by hybridization, but not to pretend it includes other, discrete genres. In my next post I will touch on why biography sensu stricto is actually not all over the bookshops and in publishing terms, I believe, is almost at a standstill.

Scurr says that her John Aubrey: My Own Life, which is published by Chatto on 12 March, is ‘written as a diary’. This suggests it is a work of fiction. But perhaps it is ‘fiction that has to fit the facts’, as Rayfield put it. Judging by Kelly, who has evidently read it, Scurr’s ‘centoic, diaristic method’ actually employs only Aubrey’s own words, taken from the vast corpus of his writings. But how do we know?! Presumably Scurr explains that in a preface. Similarly, can a biography sensu stricto be written not in the third person? If it is written in the first person, is it not by definition subjective? Where is the sense of objective factual detail, contextualisation, evaluation; of the outside ‘other’ who is the biographer? Doubtless all these questions will be resolved when we have read Scurr’s ‘biography’ of Aubrey, which clearly we must rush out to buy.

Next entry: Who was George Calderon (again)?

Who was George Calderon (again)?

I first posted on this subject last year, 13 September. The reason I am touching on it again now is that a follower has very kindly sent me a cutting from the International New York Times of 23 January which is about biographies of people who (like George Calderon) have never had biographies written of them before.

In this article, Thomas Mallon calls for the first biography of American writer Tom Wolfe (still alive at 84), and Ayana Mathis calls for the first biography of American ‘novelist, cultural critic, and jazz and blues scholar’ Albert Murray, who died in 2013. They both make out excellent cases, but I don’t think publishers are going to rush to take them up.

Since Wolfe is still alive, what publishers will really want is a sensational autobiography, whether ghosted or not, and pace Ruth Scurr (see my post yesterday) autobiography is not a department of biography. With Albert Murray, I fear, few publishers will get further than a bemused ‘Who was Albert Murray?’.

These are two reasons why our own bookshops are not awash with new biographies in the sense of biographies of people who have not had biographies written of them before. Books about people’s lives may have outsold history in Britain last year, but those books consist almost entirely of celebrity stories of the living, memoirs (fictionalized or not), and ‘new’ biographies of people who have had biographies written of them before.

I know this myself from regular forays into Waterstones and Blackwells over the past year. I would say that 95% of the ‘new’ biographies are of very well known people who have had biographies of one sort or another written of them before. For instance, in the context of WW1, Sassoon, Owen, Brooke, Thomas, but (I think) no-one who is not ‘iconic’ already. And this is hardly surprising. As publishers have written to me, George Calderon’s life may be ‘vibrant…full of action…poetic…remarkable…very human’, and his self-sacrifice luminous, but if they can’t sell 6000 copies they are not going to publish it.

Naturally, as the author I believe they can sell more than 6000 copies of an innovative biography of an Edwardian genius, but as a one-time businessman myself I perfectly well understand why they may not take the risk.

It seems to me dreary and unintelligent to keep bunging out ‘new’ biographies of, say, Shakespeare, Dickens, Austen or Vita Sackville-West, when these contain hardly any new facts that can’t be found in previous biographies. But, of course, we mercifully do not live in a command economy and well-written ‘new’ biographies of such ready-made celebrities are relatively low-risk!

I would be the first to agree that a biography that contains no new facts but presents a fresh interpretation of its subject, is valuable. But you hardly ever find that in full-length biographies of, say, the celebrities named in the previous paragraph. Thanks to John Aubrey, I was seduced into presenting my own take on Chekhov (Hesperus Press, Brief Lives, 2008), but that was because, after forty years of living with Chekhov, I was bursting to say certain things about his works and life that I think had not been said before. I would never have dreamt of writing a ‘new’ full-length biography of Chekhov, as I couldn’t have added many new documented facts to those in the full-length biographies by Simmons (1963), Hingley (1976), and Rayfield ( 1997). Incidentally, the fifty or sixty Russian and European-language biographies of Chekhov that already existed could not hold a candle to the last three, but Simmons, Hingley, Rayfield, and even Miles, were fortunate in that the demand for biographies of Chekhov already existed…

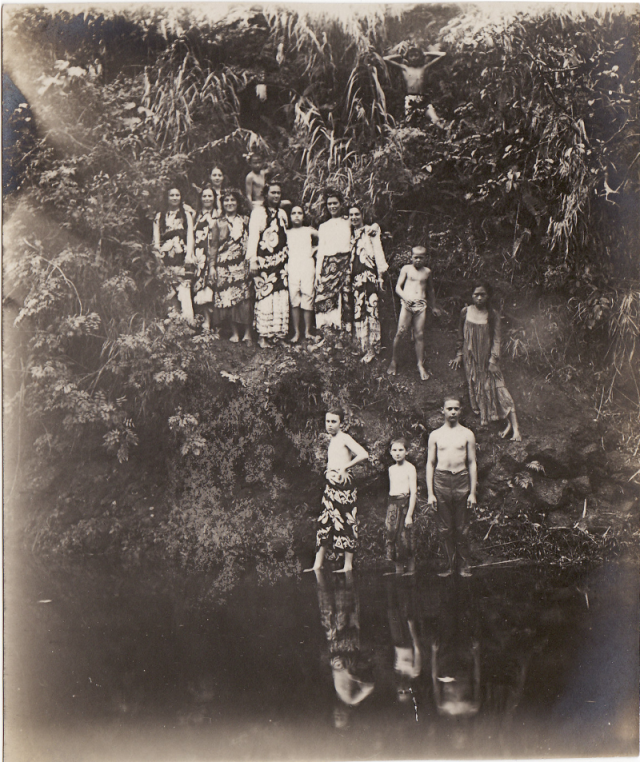

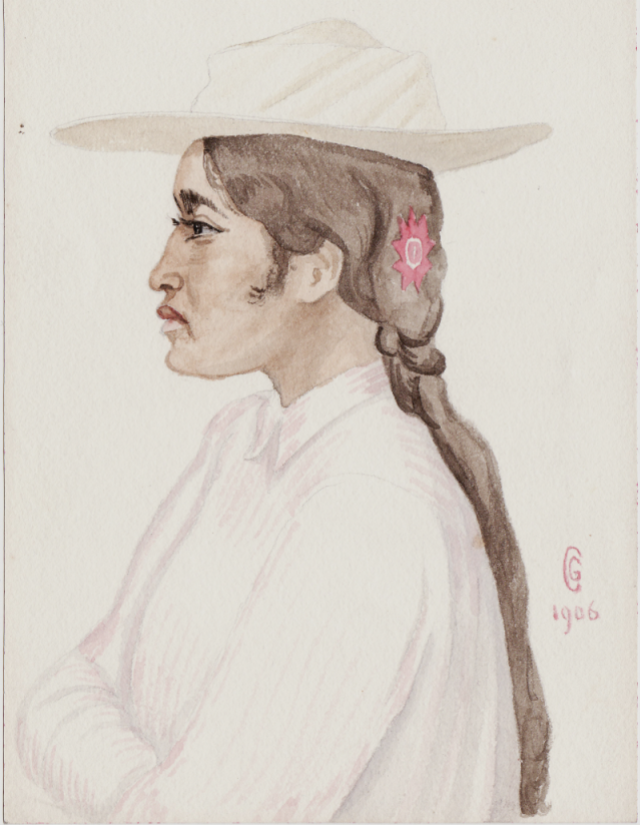

If there is no ‘demand’ for a new biography, in the sense of a subject of whom publishers ask ‘Who is he?’, then they are not going to take the risk of publishing it. I still have a long way to go with publishers and I’m certain that by hook or by crook George Calderon: Edwardian Genius will eventually be published — with, even, its full complement of illustrations. But the above, I submit, explains why commercial publishing of genuinely new biography is almost at a standstill in our country.

Next entry: 8 March 1915