Windmill Hill Camp

Monday

Beloved little Mrs Pete

I saw you on the platform long after you had lost sight of me. I could see you blindly waving till the train turned and bent me away. I met [Surgeon-Major] Pares at Basingstoke and arrived at almost eleven o’clock after a very slow journey. Everybody else had been back 24 hrs before, or nearly; many roused in the night and flying on motor cars.

My nose is out of joint as an interpreter — 3 more have arrived in the regiment; and the Brigadier and everybody has them. We have a band with a large white INT on it on the arm.

We put on all our fig [uniform and gear] this morning for inspection and to be ready: but here we are still at 2.20 p.m. still in the dark, liable to go off at any moment, all packed and saddled, playing cards, mooching about, reading papers. A lot of ladies about; they were let in to lunch, which never happened before.

I am jolly glad I have got just in time into B squadron. They gave me a fine black warhorse (almost the only black regular warhorse in the regiment — an officer’s charger) that rocks like a rocking horse, full of spirit, broad and strong and good natured, that nibbles and noggles when you stand at his head. He has a great big bold rocking action when you ride, and I had the infernal luck to jog my back again climbing up a bank with him and I’m as stiff as an ironing-board again. Never mind; it’ll be well again in a day or two, and I’ll give it a good rest in my bunk, or get somebody to rub it right in Southampton.

Goodbye my little love; live like a dog and never think of me except at 9 of an evening. Goodbye.

(Ever since their courtship, Calderon had been inclined to believe in the therapeutic power of thinking of each other at an agreed time.)

It was a packed day for him. In addition to the military preparations and writing to Kittie, he wrote to his mother — who was back in St John’s Wood — and drafted a long letter to a newspaper.

He told his mother that he was very pleased to have been transferred, at his own request, to a ‘jolly’ squadron with an Irish captain and Scots NCO, and to have been given the Hussar Paterson as his permanent servant, who would groom his horse, which was a ‘genuine old black Blues’ charger’. ‘It was capital and friendly of these fine fellows to find me such a good horse.’ He finished: ‘Goodbye to you, dear Mother, and to the family. The Germans are nearly beaten now.’ Whether he believed this is doubtful. He may have said it because he knew Clara was a compulsive worrier: as an Oxford undergraduate he had had to persuade her that rowing and hill-walking were not lethal activities.

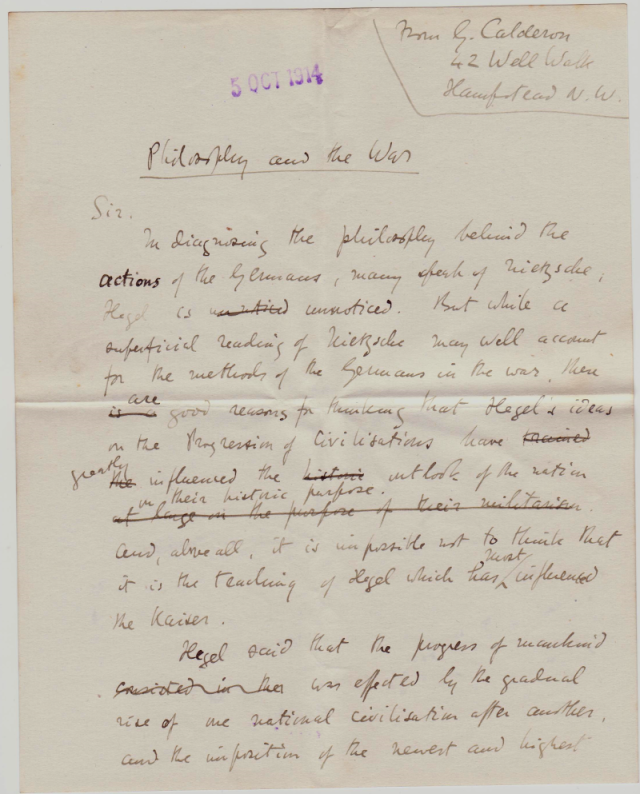

The departure point of George’s letter to the press, date-stamped this day possibly by an army censor, was that the Tsar and the Kaiser were professed Hegelians who believed in ‘the imposition of the newest and highest [national civilisation] on the world at large’. This argument, which had echoes of George’s paper ‘Russian Ideals of Peace’ to the Anglo-Russian Literary Society in 1900, was widely believed in Europe. The ideology, as we might put it, that the Tsar sought to impose on the world was thought of as Panslavism, Slavophilism, Russian Orthodoxy, or at least Russian nationalism. ‘It would be a poor office for the Belgians, French and British if we were fighting merely to set up a Slav world-domination instead of a Teutonic’, wrote George from Windmill Hill Camp.

In fact there was already widespread opposition in Britain to the alliance with autocratic, anti-Semitic, repressive Russia. But as Jonathan Haslam has written, ‘even at its most self-consciously Slavophile, [Tsarist] Russia never held itself up as a substitute model for capitalism and democracy in the very West itself’ (Russia’s Cold War, Yale University Press, 2011, p. 394). That, of course, was to come after the next World War. In a way, then, one could claim that George was prescient. The letter was signed pseudonymously and does not appear to have been published anywhere. Nevertheless, it is evidence that his thinking about the war, and hence his reasons for joining up, were geopolitical well before his recorded pronouncements of 1915.