Up at 3.30 to go out on a Patrol with [Sergeant] Mackintosh, to see that the country was clear of Germans for the Regiment to move. Out (with a little cocoa inside) between misty grey fields; very keen eyed at first, searching horizons for picketed Uhlan horses or remains of campfires. Less lynx-eyed as the sun came up. Villages rushed to the road to see us.

All through the night cars, taxicabs and London omnibuses had been passing their billet, full of Belgian and probably some Royal Naval Division troops making for Ostend, as well as refugees. Now the patrol was met by ‘masses of wagons going in still another direction; the transport of a whole division’. In fact five divisions of the Belgian army were fleeing Antwerp westwards, partly via Ghent, to take up defensive positions along the Yser canal that ran down to Ypres.

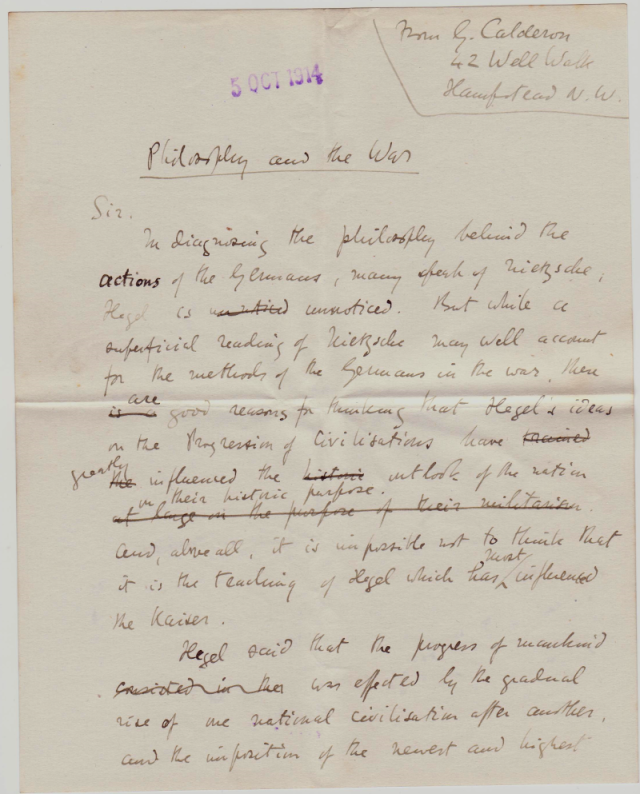

The Blues were looking to move southwestwards today along the road to Torhout (ten miles distant). As it happened, the German 4th Cavalry Corps had been active for five days over a wide area thirty miles south of there, but were now withdrawing. Calderon and Mackintosh (who dubbed him ‘The Professor’) seem to have ridden almost as far as Torhout, found no sign of the enemy, and got back to base by 9.00 a.m., where they had ‘a bite and nap’. At noon the brigade moved off.

George was beginning to experience the almost ‘comic’ contrasts, as he put it, that the war was throwing up. That evening they emerged from ‘pitch black woods’ into ‘a park with a Château’. It was ‘quite like a thing in […] a novel about a war’:

A real château, with a handsome young proprietor, in riding breeches and his father-in-law in patriarchal style. The men bivouacked in the park just outside; we slept on the floors of a group of 3 boudoirs with glass chandeliers, with a log blazing in the chimney, on the soft piled carpet. Dinner with piled fruits and long-stemmed wineglasses. I dined with wise ones in the kitchen, near the base of supplies. […] The squire’s mother avers that the Germans are only ten miles away and begs us to induce her son to fly.

The beautifully stilted phrases of the last sentence indeed make it sound like romantic fiction!

Judging by Dick Sutton’s diary, this château was a couple of miles south of the village of Ruddervoorde; i.e. they had not actually reached Torhout this evening.

Next entry: Pause and enigma

Language issues again

The version of Binyon’s ‘For the Fallen’ published in The Times (see my post of 21 September) seems to contain a misprint in line 11: ‘stanch’ instead of ‘staunch’ (‘to the end against odds uncounted’). Last week I was in the Chapel of Trinity College, Oxford, to see the College’s manuscript of the poem, and this confirmed Binyon had written ‘staunch’. But, well, the idea of a misprint in The Times in 1914 seems incredible!

I now discover from The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles that at that time there were not only two spellings for the adjective, but two pronunciations: ‘stawnsh’ and ‘starnsh’. I would have said that ‘stanch’ is used today only for the verb, and, incidentally, that the consonant combination ‘ch’ is pronounced in both spellings as in ‘church’. However, I see from The Chambers Dictionary (2009) that I would be wrong on both counts…

In his letter of 29 September 1914 George Calderon starts to tell Kittie that ‘the Ritz Hotel at Paris is somehow at our disposal and we can have things sent, which will reach us’, but then breaks off: ‘I am too bewildered with tabloids and cigarettes to go into the details.’

Tabloids? Were the Northcliffe press onto him for impersonating a soldier?

It turns out that in Edwardian times Tabloid was a registered trademark for medicines manufactured in compressed/concentrated form by Wellcome and Co, but then (rather like ‘hoover’) it dropped the capital letter in order to be used of such drugs in general. The idea of George having taken so many of these ‘tabloids’ (what were they for?) and smoking so much as to be ‘bewildered’ casts an interesting light on his state.

Next entry: 3 October 1914