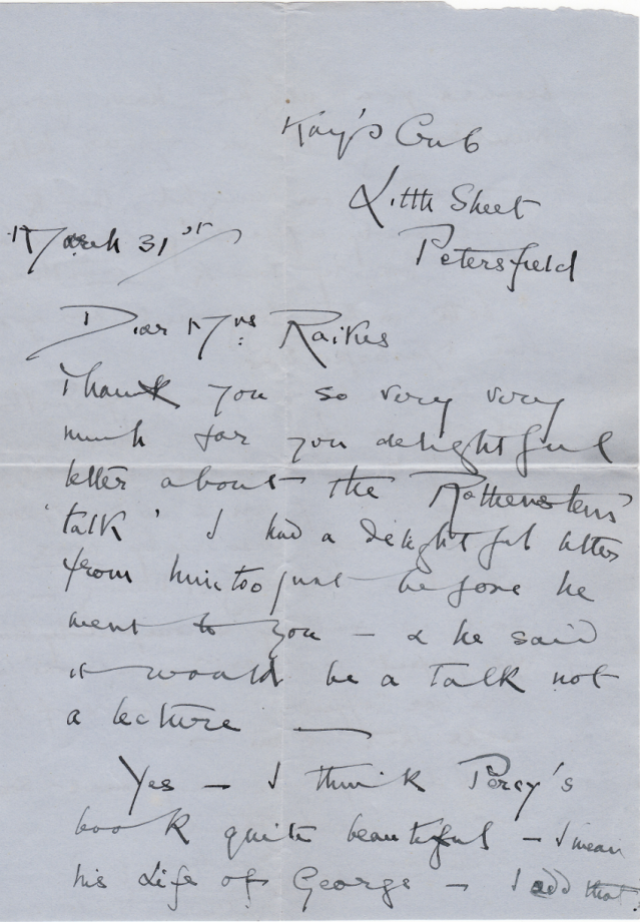

Figure from Gauguin’s 1899 painting ‘Tahitian Women with Mango Blossoms’ (left); George Calderon’s pencil sketch ‘Manu’ (right)

It must have taken great self-control for George to concentrate on making a full synopsis of his book Tahiti when he was home on weekend leave, rather than simply keep writing it. But it was certainly the most rational approach. It must also have taken him a long time, as it had to be detailed. ‘Some parts of the book were practically finished,’ Kittie wrote in her Preface (1921), ‘others existed in many forms [my italics].’ Then there were diaries and ‘papers’ from which she had to make ‘direct selections’, and ‘very often the same matter was found in different versions’. In the synopsis, he had to make the source of the various elements of the composition that were to be fletched onto the timeline as clear as possible. What Kittie made from his synopsis is a masterpiece.

Although I have a whole chapter in my biography devoted to what he did on Tahiti in 1906, reconstructed from both his own account and information kindly supplied to me by the Tahitian authorities today, I shall not be looking at Tahiti as a work of art until I get to the year 1921 in the chapter I am about to write — about Kittie’s life 1915-22. I will be very short of space, but I have been re-reading and thinking about the book for years, so it will be a huge pleasure to commit my conclusions to paper.

Tahiti has a clear set of strands: the ‘road’, Tahitian people, music, pre-Christian religion and customs, the French administration, ‘getting back to nature’, rampant sectarianism, the baleful touch of ‘Civilisation’… But from the literary point of view, the most interesting question is: how fictive is this ‘travelogue’? When I researched the biographical Tahiti chapter, it soon became clear that George had changed certain names, e.g. of the ship he arrived on and French officials. But his own note, reproduced by Kittie in her Preface, suggests something rather different:

Everything set down in this book is true. I have thought it important, for a right understanding of individual lives, and thereby a conglomeration of detail, to give a picture of the whole, to put down personal details which I have been told or found out about people. The only untruth is that I have sufficiently disguised the personality of those of whom they are told, so that no one should recognise them.

Unless ‘personality’ meant for Edwardians something closer to ‘identity’ (which is not confirmed by dictionaries), George is saying that not only did he change people’s names, he changed their characters. Does this mean that, for instance, the unique, idiosyncratic, charming Tahiri-i-te-rai and Tupuna were not in fact like that? The suspicion reminds me of our discussion a few days ago about when is a biography actually fiction!

Just possibly, one can see this at work in some of the pencil sketches and watercolours that he produced. Perhaps the reason he did not intend the watercolour I showed in my blog of 27 February to be published, and did not put the woman’s name on it, is that it was imaginary — his private idea of what Rarahu, the heroine of Loti’s Le Mariage de Loti, looked like? Compositionally it has several resemblances to Loti’s own drawing. Then I have long been intrigued by the sketch entitled ‘(Manu)’ that Kittie included in Tahiti. This is the sketch I have reproduced above right. In technique, intensity and wistfulness it always struck me as different from the rest. Then about three years ago I suddenly realised it reminded me of the figure in the left of Gauguin’s 1899 painting ‘Tahitian Women with Mango Blossoms’ — the figure reproduced on the left above.

We know that George was deeply interested in Gauguin’s art, because he visited the famous First Exhibition of Post-Impressionist Paintings in London in 1910, which included thirty-six of Gauguin’s paintings, and wrote about it in the New Age. ‘Tahitian Women with Mango Blossoms’ was not shown in that exhibition, and I have been unable to track its ownership from, say, 1906 to 1914. But could George have seen a reproduction after he got back from Tahiti and drawn ‘(Manu)’ then, because he was reminded of her by the Gauguin figure? As with the ‘Rarahu’ painting, there are some distinct resemblances. It is also interesting that he has put ‘Manu’ in brackets, as though it was not ‘really’ her, not actually done from life. Not all of the drawings/paintings reproduced in Tahiti have the names of their sitters on, but ‘Manu’ is the only one enclosed in brackets.

The other thing we have to remember is that the writing of Tahiti was an act of creative hysteresis, i.e. the creation came years after the cause. So, as Kittie stresses, it was a work of memory…and memory of course massages fact. Although it contains its barbed wire, syphilis, and brutes, is the Tahiti of George’s book an imagined world, a fictive one, and how close are those qualities to imaginariness and fictitiousness?

I have a predilection for this image of Tahiti myself, because in the winter of 1972/73 in Moscow, surrounded by informers, KGB microphones, queuing, freezing fog, lies and mass psychosis, I came across a Soviet reproduction of ‘Tahitian Women with Mango Blossoms’ in a pack of postcards sold at a tobacco kiosk. Along with other ‘icons’, including sensu stricto Rublev’s ‘Trinity’, I stuck it on the snot-green wallpaper above my work table in the student hostel on Lenin Hills.

People will say that it is quite obvious what the ‘message’ of this painting is from the central position of the blossoms and the breasts, but in my experience your eye very quickly fixes on the girls’ faces, which are so different, yet filled with the same gentleness, nobility, and security. The painting, even in this oddly coloured reproduction, helped me survive a year in the Soviet Union as a postgraduate.

Soviet postcard reproduction, c.1970, of Gauguin’s ‘Tahitian Women with Mango Blossoms’

Sometime in 1973 I wrote:

Those girls, they stand there simply, offering

perhaps the future, or the murdered past.

Oh love-red blossom, and on golden skin

ash blue and faded mauve and deepest Pasque.

She is still giving, strongest trust; yet looks

a little to the side, beyond us here.

The other whispered softly to her, coaxed,

but almost hides her own pale, thornless briar.

(First published in Iota, no. 37, 1997)

Next entry: 15 March 1915: The strain tells

Biography and the limits of non-fiction

I keep dipping into Ruth Scurr’s John Aubrey: My Own Life. It’s very compulsive reading, but I don’t have time at the moment to let it run away with me as I would wish. Nevertheless, I’ve read enough both of the ‘diary’ Scurr has produced and her Introduction to be able to say that they certainly challenge received ideas about biography. I shall try to get to grips with her innovativeness before long, but in the meantime any follower who has read Scurr’s book is very welcome to get the ball rolling by leaving a Comment to this post.

In my post of 6 March I touched on several issues that Ruth Scurr raised in an essay in The Guardian, but underlying them all was my wariness, unease, about bringing biography closer and closer to fiction, in fact novelising it. I fret equally, though, over the opposite question: whether a biography can be one hundred per cent non-fiction — whether it is possible to keep elements of fiction out!

Take my last two posts. They are predicated on the ‘fact’ that George Calderon was home on leave from the 9th Battalion Ox and Bucks at Fort Brockhurst from Good Friday to Easter Monday 1915. My reasons for believing this are:

1. Kittie in her memoirs says he regularly came home ‘for Friday-to-Monday leave’.

2. I would expect him to want to be home with her at Easter.

3. The very last of George and Kittie’s 247 books to be found (2013) is Thomas Sturge Moore’s Hark to These Three Talk about Style (London, Elkin Matthews, 1915), and in the front is the inscription: To Mr & Mrs Calderon a token of a neighbourly Easter from the author. 1915. For the Calderons’ close relations with their neighbours the Sturge Moore family at 40 Well Walk, see my post of 20 November 2014 and others. It seems unlikely that Sturge Moore could have written this inscription if both George and Kittie were not there to give the book to.

Yet it takes, perhaps, a conscious effort to remind oneself that it is still not a FACT that George was at home at Easter. For that one would need a dated letter or document to say so. Thus non-fiction has here effortlessly drifted into fiction…or fiction effortlessly crept into non-fiction. And it is all too easy for the biographer to let this happen.

Sturge Moore’s book, incidentally, is a veritable repository of Edwardian aesthetics. There is no evidence that George read it, but I would dearly have liked to know what he thought of it. There is evidence that he found the whole notion of ‘style’ dubious. He seems to have felt that the man was the style and the man had to have something to say. In January 1899, when Kittie and he were sharing their critical views in correspondence, he wrote:

Next entry: Two separate biographies