In my 22 January post I explained the meaning of the Edwardian verb ‘to apple’. I mentioned that five lines in George’s letter to Kittie of 10 May 1915 were ‘appled out’ and I was following up ‘forensic programmes’ for reading beneath crossings-out.

Unfortunately, consultation with a retired Chief Constable revealed that the police don’t have such ‘forensic programmes’. They too are dependent on magnifying glasses, lighting, Ultra-Violet lamps, digitalised imagery and traditional methods of deciphering handwriting. Since January, then, I have tried all that, with the help of my own computer and of UV equipment belonging to the Manuscripts Department of a local museum.

The most productive method has been the ‘traditional’ one: constructing on paper a grid of the lines of writing and the separations between words (as far as one could ascertain these spaces), then trying to read George’s writing beneath Kittie’s ‘appling’ at irregular time intervals, with a magnifying glass, and with lighting of different intensities at different angles, then transferring what one could make out to the grid. It is surprising how differently one sees the appled out writing each time one comes to it afresh.

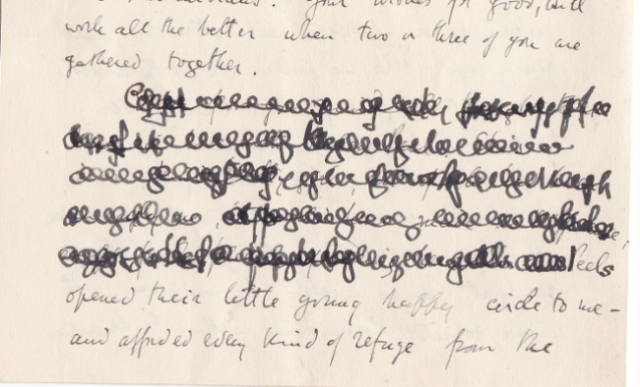

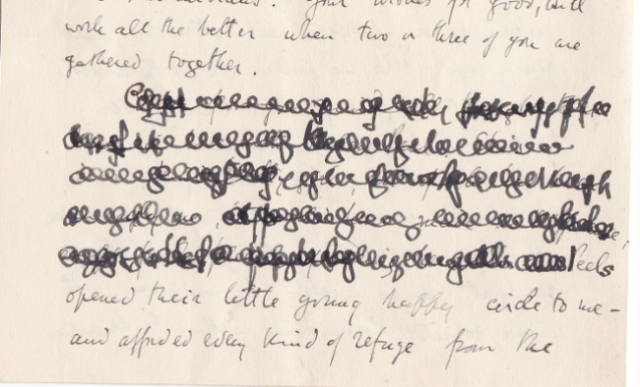

Even so, because George’s pen is very fine and his ink faded, this is all that to date we have been able to identify:

The original five appled lines

What we have so far

If anyone can decipher more, or has any suggestions about how we might tackle the problem further, please say so in a Comment asap!

In my January post I wrote that the ‘appling’ in George and Kittie’s letters raises the question of breaching their privacy — as it were their ‘trust’ in me as their biographer. Everyone who has discussed this with me in the case of this letter has said they think we should attempt to de-apple these lines. But that might be just because they are nosy!

My own view is not Aubreyan. I don’t believe the biographer’s job is at all costs to seek out the sensational and salacious, which Aubrey erroneously called ‘the naked and plain truth […] exposed so bare that the very pudenda are not covered’. Such ‘naked and plain truths’, which are actually just facts, may not be typical, or at all important in the big biographical picture. To focus on them might just be prurient.

I believe it is a question of perspective. Admittedly, this is itself a very personal matter. For instance, it was very important to Percy Lubbock, writing George Calderon: A Sketch from Memory for Kittie in 1920, to focus on George’s war experiences and letters from the two fronts; so much so that they make up a fifth of his book. I devote only a tenth to George’s year as a soldier, because my perspective is more holistic or, to be honest, skewed towards George’s writing, thinking and activism in the rest of his life. In that context, a few lines appled out here (before the letter was shown to George’s first biographer, Lubbock), or in George’s love letters to Kittie (which Lubbock did not see at all), may not be very significant — although I agree that the biographer has got to know what is appled out before he/she can decide how significant it is.

Finally, you of course must discuss such issues with the descendants of those people who feature in your biography. You are not a tabloid journalist. The living descendants will have sensitivities and a view of their own, which you must respect. I am delighted to say that in the case of key players in George Calderon: Edwardian Genius, their descendants and I are in absolute agreement. On the one hand, ‘a hundred years is a long time passed’, as one expressed it to me; on the other, what one is after is a true perspective.

Today the Battle of Festubert was launched on the Western Front between Neuve Chapelle and La Bassée. It was the first British attempt at attrition and about 100,000 shells were fired in the first sixty hours. The front wavered back and forth for the next ten days. British casualties were 16,700, German approximately 5000. By the end of the offensive the line had advanced two miles and British forces were completely out of shells.

Next entry: 16 May 1915

28 May 1915

It may have seemed surprising, or even shocking, that Calderon did not end his letter to Kittie yesterday with any endearments to her, only a ‘warm embrace’ for their dog! But its beginning — ‘Oh dearest Mrs P.’ — is very immediate and seems to speak volumes. Moreover, the simple ‘P.’ with which he signs off has a circle drawn round it, signifying in Edwardian emoticons ‘I hug you so tightly my hands meet on the other side’.

Even so, the letter itself seems thoroughly low-key, even dull (‘I am beginning to repeat myself’). I am convinced that this is deliberate. It is an attempt by a wordsmith of great cunning to lull Kittie into thinking not much is happening, that he is leading a completely routine army life, and above all is in no danger whatsoever and never will be. The truth was quite different. At this point in the campaign you could not walk from Helles to the front line concealed in wide communication trenches. The camp George was at was in the open, exposed to shelling from Achi Baba and the Asian shore, as well as stray bullets, although it did include a number of trenches and dugouts. The reason he was being instructed in ‘bomb throwing from trench to trench’ was that the Turks had used grenades to devastating effect but the British had only just started making them (from jam-tins). All sources agree that the torpedoing of the Majestic at Helles yesterday and the rapid withdrawal of the battleships to Imros and Mudrops had a depressing effect on the troops. Finally, if Hamilton decided to fight a Third Battle of Krithia, there was absolutely no doubt that the KOSB would be in the front line.

A writer to whom I showed the 1914-15 chapter of my biography back in April responded: ‘All his mishaps and frustrations in trying to get where he wanted to be are entertainingly described — then the note darkens.’ I had hardly been aware of this myself, as I was just ‘showing it as it was’, but it is true. There are touches of Calderonian comedy in his descriptions of the clerics on board the Orsova, but on Gallipoli his humour (when it surfaces at all) is black. Here is an example from yesterday’s letter:

The precarious paradox is quintessential Calderon (see my post of 12 April), but one feels that at a deeper level the ‘joke’ is a defence mechanism. As we shall see, escape into the beauty of the landscape, the smells, sounds and sights of nature on the peninsula, was another form of defence mechanism for this super-refined man at the killing fields, pretending to be just one of the troops.

Next entry: ‘Nothing happened’